If you’ve ever used advice you got from a successful person’s book, video, podcast, training course, or website, you may have fallen victim to the Dexter Effect.

Some of this advice can be extremely useful, but some of it is highly suspect. Unless it includes certain positive telltale signs, your best bet is to nod politely, say “thank you,” and then ignore it completely.

In the late 18th century, near the end of the American Revolution, there was a very eccentric businessman named Timothy Dexter in the Boston area who had brought himself out of poverty through a combination of the leather trade and marrying a wealthier woman. He was a confident guy, thought highly of himself, but had a shortage of common sense, and so his neighbors, who disliked him, enjoyed messing with him by giving him very stupid business ideas.

If you’ve heard the expression “selling coals to Newcastle” (I had to look it up), you probably know it means, in short, doing something foolish. Newcastle was at one time a huge producer of coal, so bringing coal there to sell isn’t likely to be profitable. It’s about on the level of selling ice at the North Pole.

Well, when Timothy Dexter announced to some drinking buddies in Newburyport, Massachusetts that he was looking for a new business idea, someone said, “Hey, you should ship some coal to Newcastle!” and the clueless Timothy Dexter filled up a ship with coal, and sent it along.

So, just to recap, Timothy Dexter was now unwittingly re-enacting an expression meaning “throwing away your money,” and of course everyone expected he would take a severe loss. The ship arrived in Newcastle, and the captain (who I guess must have either been in on the joke, or a bit out of the loop himself) discovered that the coal miners were on strike. So Dexter’s shipment of coal sold for a massive profit.

This happened to Dexter again and again. Someone told him he should sell mittens and warming pans (basically the 18th-century equivalent of an electric blanket) in the Caribbean, where they surely couldn’t have been in high demand. When they arrived, another merchant on the way north bought the mittens, and the warming pans got repurposed as ladles for the sugar plantations. Again and again this guy made staggeringly idiotic business moves and somehow lucked out on them.

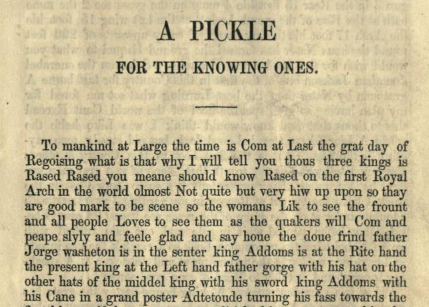

As you might expect, being apparently invincible in business gave him an even higher opinion of himself, and later in his life he decided he’d better share his wisdom with the world. (This was shortly before he faked his own death in order to personally supervise his funeral.) He wrote a book called A Pickle for the Knowing Ones, or Plain Truth in a Homespun Dress. Here’s the beginning:

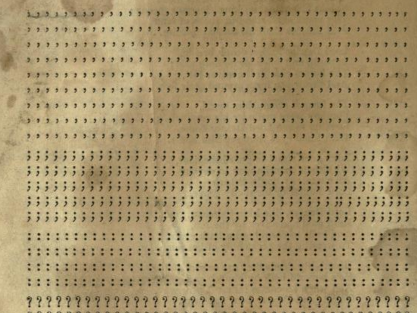

It had almost 10,000 words, but hardly any punctuation marks. When people complained, he added an extra page at the end of the second edition covered with commas, dots, and semicolons, with a note to readers to “peper and solt it as they plese.”

Timothy Dexter, for all his eccentricities, was a very wealthy and well-known man. If I were to give you a copy of his book, highly recommended, would you eagerly look through it for advice on making money?

I’m going to guess not. Most people wouldn’t.

But why?

You can’t dispute that he was very successful in business. But his successes were the result of dumb luck, not special knowledge of understanding. He did well not because of the choices he made, but despite them.

Timothy Dexter is an extreme example, but the Dexter Effect shows up everywhere in the world of management and business. When someone has been very successful, and has written a book of their opinions about how you can do it too, it’s intensely tempting to follow their example — yet it’s incredibly difficult to tell whether they did well because of those opinions and choices, or despite them — whether they were brilliant, or just lucky.

For every Timothy Dexter who made a fortune, there are hundreds or thousands of Timothy Dexters who crashed and burned. We never hear about the ones that shipped coal to Newcastle, and no one wanted it, and they went bankrupt. We never hear about the ones that bought a worthless currency at the wrong time, and lost their fortunes. No one talks about those Timothy Dexters, and they don’t write books. We hear only about the lucky ones, and we assume it wasn’t luck at all, but skill. Telling them apart from the truly capable ones can take a great deal of effort.

We devour management books by famous CEOs and entrepreneurs. We take their ideas and their stories and apply them to our own careers, without demanding any further evidence, and without stopping to examine whether this is a case of because, or despite.

Another way to think about this: imagine we’re playing a simple game. We’ll call it the Coin Toss Game. The rules: you flip a coin 10 times, and if you get heads 10 times in a row, you win. The chances of this happening are a little under 1 in 1,000, so, if you play this game, unfortunately you’ll probably lose.

But suppose we’re playing the Coin Toss Game in a room full of people – around 2,000 people, in fact. With chances of 1 in 1,000, it’s very likely that one or two people will get heads ten times in a row, and win the game.

What are people going to say about the winners? Will they mob them at the exits, take selfies, and beg them to share how they became such good coin flippers? Will they ask when the books My Life in Coin Flipping or Secrets of a World-Class Coin Tosser will come out?

No, because in this case it’s obvious that luck was the main factor.

Let’s be clear: I’m not saying skill and experience never has a role. I’m saying the bulk of business, entrepreneurial, and management advice is fluff, and there’s a rare key ingredient you need in order to be sure what’s what.

The key ingredient is evidence.

Using evidence to make decisions is a familiar idea in many fields, like medicine, but elsewhere expert opinion and hearsay still rule.

Evidence is not black and white – it’s a spectrum, ranging from totally unfounded opinions (which are not evidence at all) all the way to meta-analyses and systematic reviews in high-quality peer-reviewed journals, which are the gold standard of evidence, but still don’t offer 100% certainty. There is a lot of room in the middle, and it’s important to find the best evidence available on whatever topic you want advice about.

Sometimes that advice is still spotty, like three case studies of what happened to similar companies in a different industry. But if that’s the best that’s available, it’s still much better than a management book from a celebrated manager that offers opinions on how you should lead with nothing but inspirational anecdotes to back it up.

Next time you read one of these books, go through a training course, or whatever, take note of the evidence cited. Do the experts refer to scientific research? Do they cite statistics with a large sample size? Do they draw from specific experiences in a large number of relevant, diverse situations? (In books, you can check the footnotes or the back of the book to gauge the references.)

If none of these things is present, don’t worry. Just ignore all the advice, write it off as purely entertainment, and sit back and watch the Dexter Effect at work again.