Managers are supposed to know what’s going on throughout their teams, and use their greater judgment and insight to handle major decisions. But a lot of this knowledge is a mirage, or at least an oversimplification. Being conscious of this can save us from a lot of poor decision-making.

Mistakes called “cognitive biases” distort the thinking of everyone with a human brain. Overconfidence is an important one. Overconfidence is exactly what it sounds like: being more confident or certain than we should be. This can take many forms. We think we’re more knowledge than we are, or more capable. We think we can get things done faster and cheaper. One of my favorite examples is that about 80% of drivers believe they have above average driving abilities.1

We Know Less Than We Think

We’re especially prone to thinking we know more than we actually know. Our brains are ruthlessly efficient about how they store information, and will only retain what we need to get around and accomplish what we need to accomplish. Any knowledge we don’t use on a regular basis tends to get simplified out of existence, even if it’s something we’re exposed to constantly. For a few examples, try any of the following (without looking!):

- Draw the exact layout of your computer keyboard, with the keys in the right positions

- Draw an exact floor plan of your house, with all the windows, doors, walls, corners, etc. in the right places

- Visualize what your ceiling and ceiling light fixtures look like at home (if you’re out) or at your workplace (if you’re home)

- Draw an exact diagram of your favorite pair of shoes, with all the seams, holes, etc. in the right places

A study done at the University of Liverpool had subjects try to draw bicycles and found most of them couldn’t get even basic details like the positions of the chain and the pedals right unless they looked at a bike while doing the drawing. (The results were published in the cleverly-titled article “The science of cycology.”)2

In short, we walk around with extremely simplified models of reality in our heads, and our brains fill them in moment to moment with all the sensory details we experience; but we have this illusion that all of that rich sensory detail is stored away in our brains as well.

The drawer we open every single day to get out the toothpaste is just an abstract drawer in our brains. The exact shade of the wood, the shape and location of the handle, the dimensions, the texture of the inside, how far it rolls out – all of these are missing, but when we imagine the drawer it seems like they’re there.

You may be able to see where this is going. If you’re a manager, that project you assigned to your direct report is, in your brain, a vague and abstract notion – but that vague notion is hidden by an elaborate, detailed mirage.

For managers, the exact details of what a team member is doing, moment to moment – the emails, the meetings, what else needs to get done first, what’s happened so far, who else is involved, what makes it complex – all of this has been simplified out. But when you bring the project to mind, you feel very confident that you’re aware of the full details of the project and how it’s going. You feel you could rattle off a status update off the top of your head. Maybe you could even make a decision about it. This is where the danger comes in.

Have you ever seen one of those blind spot eye tests? They look something like this:

Try it now. Cover your left eye, and look directly at the blue star. Stay focused on the star. Now, move your head closer to your screen slowly. At a certain distance, the little red dot on the right will suddenly vanish.

What’s happening here is that there’s a spot in your field of vision for which you don’t receive any sensory input, because of the position of your optic nerve. Your brain basically “guesses” what’s in that space based on the surroundings. Try the variation of the test below:

This time, what you probably experienced is that the red dot vanishes, but you still see the green background where it should have been. Why? Because your brain fills in the space there with what makes the most sense given the surroundings.

You can think of this as a metaphor for what happens when a manager thinks about a project the team has been working on. Although what’s going on neurologically is different, there is a similar “filling in” process that happens, where your brain smoothly and undetectably paves over gaps in your information by oversimplifying what’s going on.

Patterns

While all of this is going on and wreaking havoc, another layer of cognitive bias is complicating things further. Let me demonstrate.

B C D

E F G

A B _

Take a look at these sequences of letters. What letter would you put in the blank?

F G _

Here’s another one. What letter would you put in the blank?

Most people, looking at the letters above, will say the letter in the blank should be ‘H’ – the next letter in the alphabet. If you have a musical background, you might have guessed that things are not as they seem on the surface, and guessed ‘A’, assuming the letters represent musical notes.

In fact, using the pattern I’ve chosen, the next letter is ‘J’.

Why? Well, here are my rules:

- Take any letter for the first spot.

- The second letter will be the next letter in the alphabet after letter #1.

- The third letter will be the next letter in the alphabet after letter #2 that has a curve in its shape.

With those rules, we can add a few more examples to the ones above:

B C D

E F G

A B C

F G J

Q R S

K L O

R S U

G H J

What happened here?

First, you assumed that there was actually a pattern at all in the combinations of letters. If you reread what I wrote when asking you to fill in the blank, I never explicitly said there was a pattern. I could have told you afterwards that ANY letter was fine, because my rule was just “three letters on one line.” But it’s very difficult for us NOT to see a pattern when the examples suggest one, as these did. Also, you probably very quickly settled on a likely pattern. This is a case of runaway pattern recognition, or “apophenia.”3

Second, you succumbed to “confirmation bias.” When you guessed the letter ‘C’ correctly (I assume) in the first example, you took that as evidence that your theory of my rules was correct, ignoring the possibility of other explanations.

Pattern recognition is one of the signature strengths of the human brain4, and being a little trigger-happy in seeing patterns may possibly even have helped the human species survive.5

But for managers, who are trying to make decisions about complex business problems and intricate team relationships (not so much avoiding dangerous animals or poisonous plants), this hasty pattern recognition is constantly sending them astray.

Imaginary Knowledge and Managers

So, it works kind of like this.

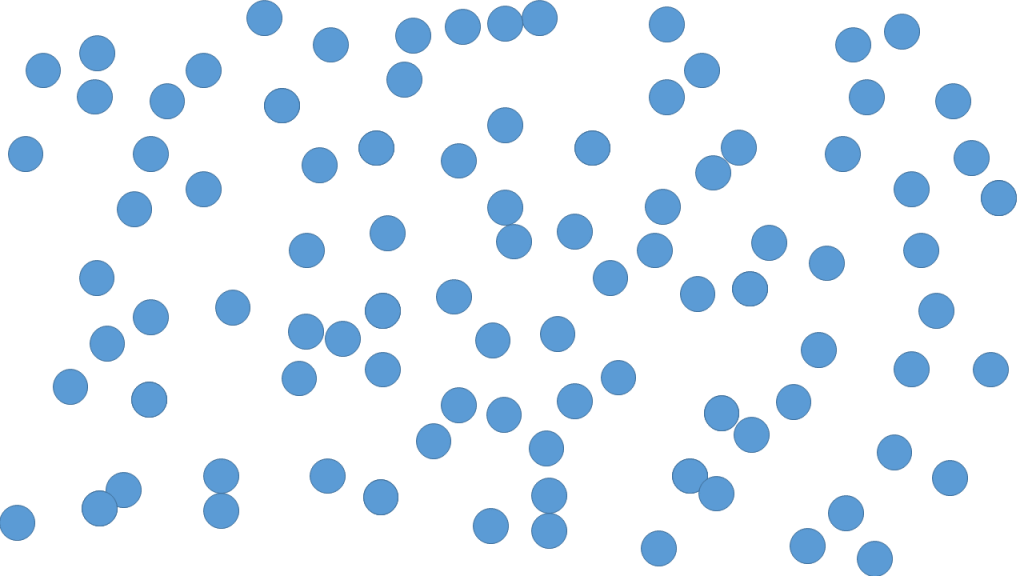

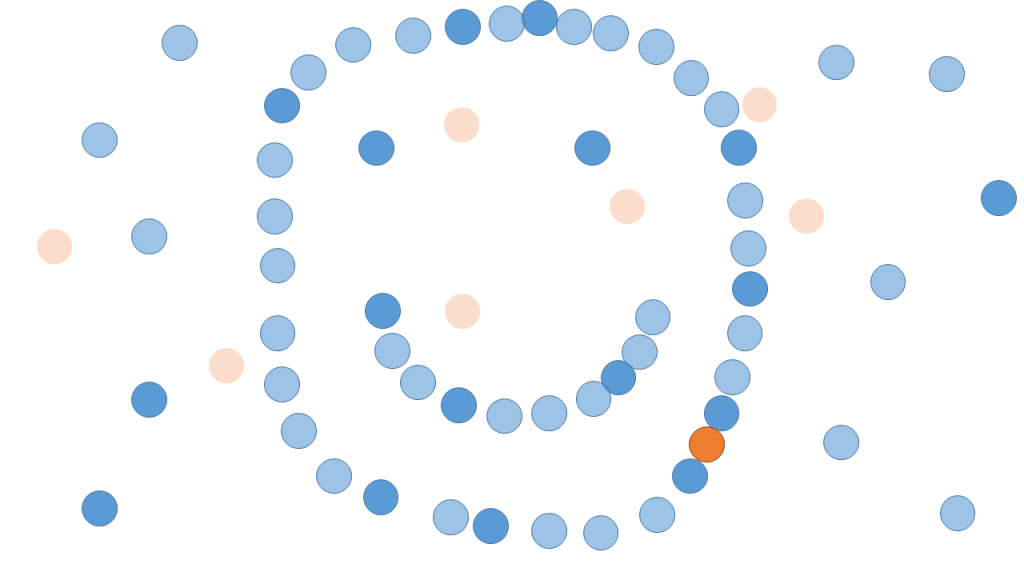

Let’s say these dots represent what’s actually going on in our organization:

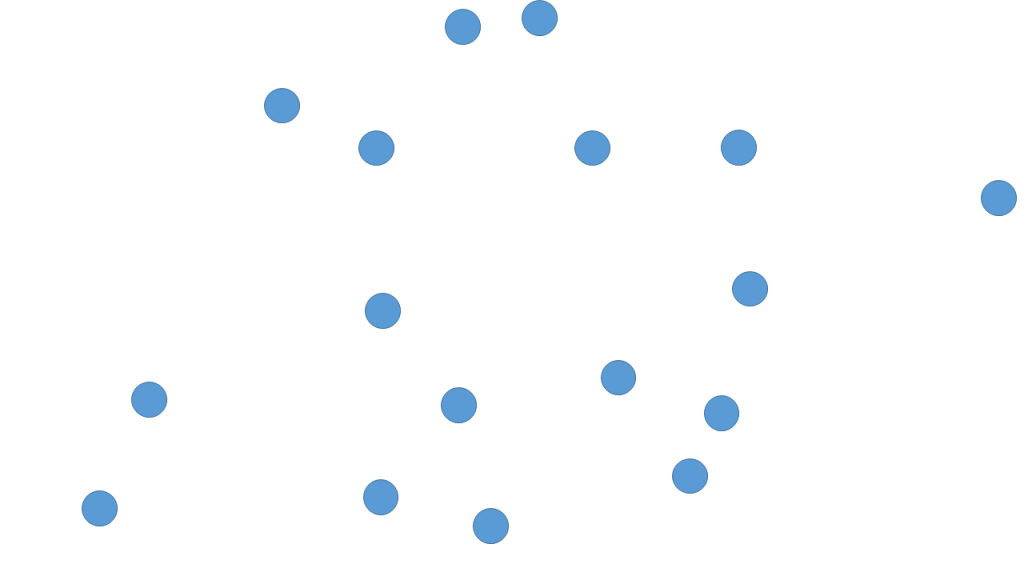

But we only know part of what’s going on:

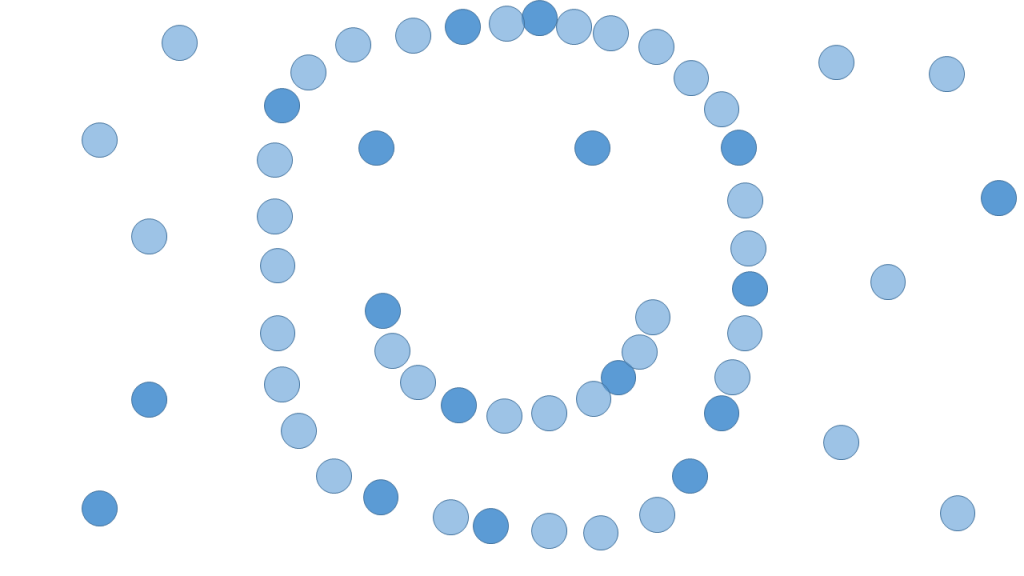

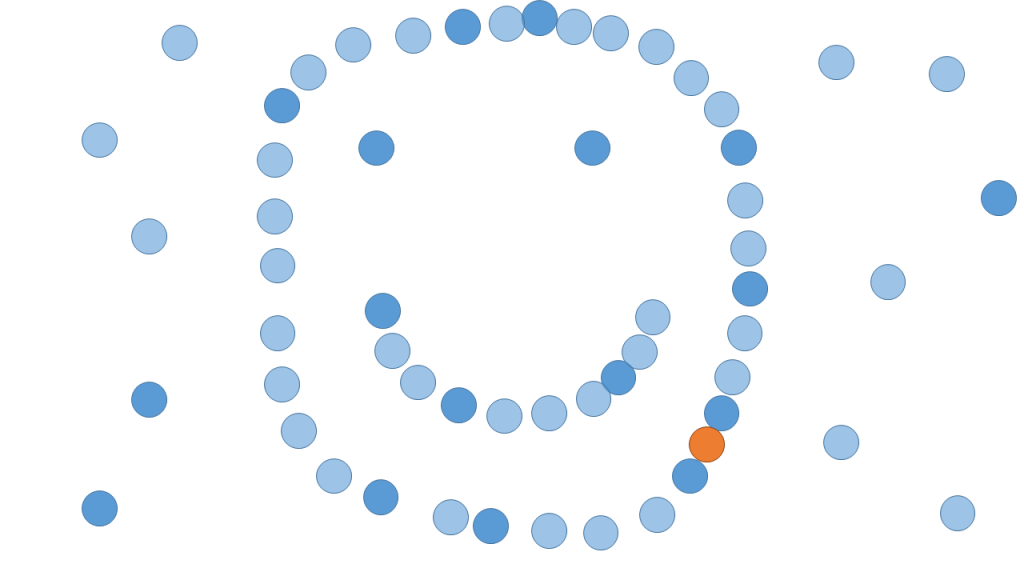

But we believe we know much more than we actually know. So our brains support that illusion by filling in the gaps with some patterns that make sense to us:

When new information comes in that fits our pattern, we slot it right in! This must be proof that our managerial judgment is correct.

If it doesn’t fit, it may even escape our notice entirely.

We start with limited awareness, overconfidence gives us the false feeling that we actually know a lot, apophenia fills in that illusion with imaginary knowledge, and finally confirmation bias uses new REAL information to reinforce our illusion.

And this is how managers can end up in situations like saying “my team loves their work and we’re running right about on schedule for the customer deadline,” only to discover a day before the project is due that half the work is unfinished and most of the team members are on the verge of quitting. Those biases that work great for avoiding a snake bite backfire quite a bit when the needs and the stakes are completely different.

What Can We Do?

This is all pretty sobering. But what can we do about it?

Some people might say “nothing.” On one level this is true: we can’t change the way our brains function, so it’s unlikely that we can eliminate cognitive biases or their effects altogether.

But there is evidence that we can mitigate the impact of these biases on our decisions and behavior.

Stay tuned for my next post for more details on how to do that. For now, just keep in mind that being AWARE of the cognitive biases you’re subject to, and how they distort your thinking, is a good first step.